UTZ Certified teaches farmers business skills to help them to negotiate, but like Rainforest Alliance, has no guaranteed minimum price or premium for cocoa farmers. The price and premium are negotiated between the farmer and the first buyer.

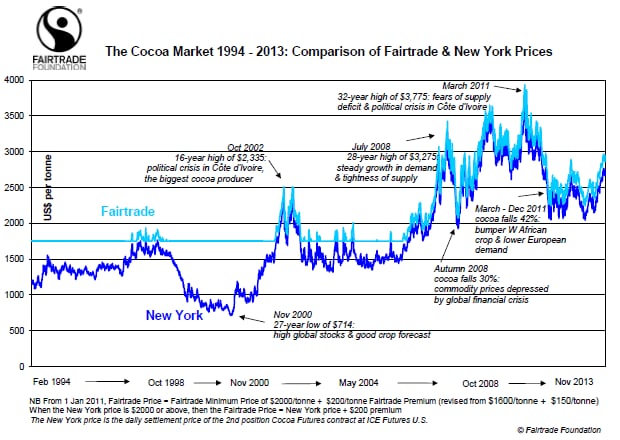

Fairtrade International by comparison has a minimum price of $2,000 per metric ton (MT) ($2,300 per MT for organic cocoa beans) and the Fairtrade premium is consistently $200 per MT even if the New York Exchange price exceeds $2,000 per MT.

UTZ: Maximizing yields is more important

Han de Groot, executive director of UTZ Certified defended his organization’s policy: “Applying a minimum price would create market distortion”

“If we want to bring good practices to scale, the market is an important pulling force. Using a minimum price is not helping that practice grow.”

UTZ Certified and Fairtrade Premiums Compared

Fairtrade certified cocoa farmers are guaranteed a $200 per MT premium, while the average weighted premium for UTZ cocoa in 2012 was €112 per metric ton ($151).

The organization head said that incentivizing farmers to maximize yields had a far greater impact on their lives than a minimum price.

“What’s much more important is how much your farm is yielding,” he told ConfectioneryNews.

Fairtrade: Guaranteed prices give farmers a safety net

Samantha Dormer, head of product strategy management for cocoa at Fairtrade International took a different view on premiums.

“Having a Fairtrade Minimum Price and a pre-set Fairtrade Premium – which cannot be negotiated or discounted – provides producers with the income stability they still need to plan for their futures.

“While market prices for cocoa have remained high in recent years, the Fairtrade Minimum Price can be invaluable as a safety net in case prices drop. We are now seeing this in the case of coffee, where coffee prices spiked in 2011 but have now plummeted and are below the Fairtrade Minimum Price.”

She added that the largest cocoa producing countries, Ghana and the Ivory Coast, had recognized the value of minimum prices for farmers by setting a minimum gate price.

UTZ: ‘Farmers still have to sell their product’

UTZ contended that buyers were not prepared to purchase cocoa for a minimum price if it was of inferior quality. The organization argued that having no minimum price meant farmers were still paid for an inferior crop, even if the premium was lower.

Chocolate makers working with UTZ Certified

Ferrero, Barry Callebaut, Cargill, Mars, Nestle and Natra

“You can set a minimum price but you still have to sell your product,” said De Groot.

We put it to De Groot that some farmers may be more equipped than others to negotiate a premium, which could create huge disparities in prices from one farmer to another.

He said that farmers’ organizations and cooperatives were important in this respect, as well as training farmers in business skills.

“I don’t think creating equality in pricing or income in countries is a viable route. It’s too easy to say that a farmer gets justice by getting the same as a colleague across the globe.”

He said there were huge variations in the cost of labor and the productivity of the land across various cocoa producing nations. Ecuador for example has developed a high quality cocoa sector that serves premium chocolate makers and farmers there deserve a better price for their quality produce, said De Groot.

“We stimulate farmers to be reliant on themselves and not on organizations.”

Mars employee says yields make a bigger difference than premiums

UTZ’s strategy was supported by Chris Cuello, director of strategic initiatives for Mars Chocolate North America, who said in a recent blog detailing his trip with UTZ in the Ivory Coast:

“What’s really making a difference is the training and investment in the farmers skillset. That is the gift that keeps giving. I have heard several stories of farmers doubling their yield and profits and that makes a bigger difference in their lives than the premium.”