Editor's Note: This is part two of our special report on price premiums. Read our analysis of the recent PLOS study proposing a specific price premium in Ghana.

Fairtrade: essential to pay farmers a fair price, but pay heed to nuance

Fairtrade, a leader of price premiums that ensure fair labor practices, told us that the organization ‘broadly welcomes’ all efforts to address the challenges farmers and workers – especially women and youth – face every day in supply chains around the world.

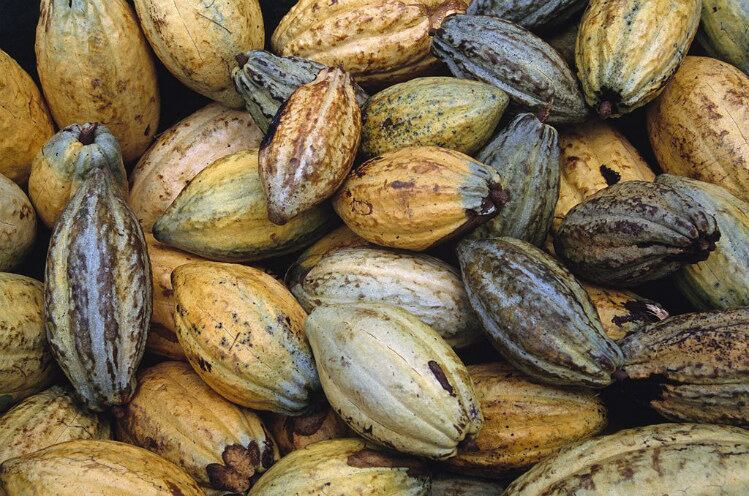

“Poverty is one of the main drivers of child labor, and we broadly welcome the findings of the recent [PLOS] study, which [supports] our position that one of the best ways to eliminate extreme poverty in the long run is to pay farmers a fair price for their cocoa so they can enjoy a decent standard of living,” Fairtade said in a statement to ConfectioneryNews.

It begged caution, however, in “assigning specific values or assuming that paying more for cocoa will of itself eliminate child labour, which is not solely driven by poverty.”

In its 20-plus years on the ground with some of the world’s most vulnerable populations, Fairtrade has seen middle-class households using child labor: “It is important to correct the commonly-held belief that only people living in poverty exploit children this way.”

The study also left unclear whether its definition of labor encompassed child trafficking, which Fairtrade called ‘one of the worst forms of child exploitation.’

Much more work needs to be done comparing the costs of cocoa farming with and without child labour before we can calculate how much it costs to eliminate. That said, Fairtrade absolutely agrees that increasing the price of cocoa to enable farmers to earn a decent income could be a major factor in eliminating child labour.

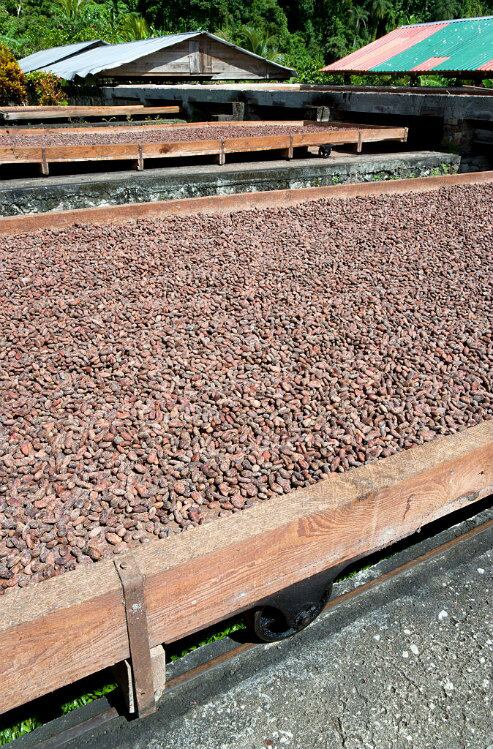

The organization also cited the collapse of cocoa prices, resulting in many West African farmers earning less than a dollar a day. That they are straining to produce the bulk of the world’s cocoa supply exacerbates this hardship: “The current broken trading system means that cocoa farmers get paid next to nothing while chocolate traders and manufacturers make big profits,” Fairtrade told us.

A 2018 study revealed that a majority of Fairtrade-certified households running cocoa farms in Côte d’Ivoire earned incomes far below the poverty line. This data compelled the certifier to increase – for the second time in two years – its minimum price for conventional and Fairtrade premium cocoa by 20%, effective in October 2019.

Fairtrade also confirmed its support of the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana setting a higher floor price of $2,600 per metric ton.

Yet none of these initiatives should exist inside a vacuum. Fairtrade, for instance, has pushed for a holistic strategy that includes increasing productivity and diversifying crops beyond cocoa.

“Fairtrade understands that raising the minimum price for cocoa will not in itself solve child labour, nor that standards and auditing are the only answer to the systemic poverty in the West African cocoa supply chain, which is one of the key drivers of child labor.

“Child labour is a complex universal issue affecting boys and girls in most countries of the world, and although poverty is the main cause, exploitation, lack of access to quality education and social protection, discrimination, conflict, HIV/AIDS and natural disasters all play their part.”

Tony's Chocolonely says it's not enough

Paul Schoenmakers, head of impact at Tony’s Chocolonely – whose very ethos hinges on eradicating slavery in the cocoa industry – told ConfectioneryNews that it applauds these initiatives but warns that they fall short of actually enabling a living income.

According to the company’s 2017 estimates, a stable living income would require a floor of $3200 per ton.

Recognizing poverty as the ‘root cause’ of illegal child labor and modern slavery in cocoa, Schoenmakers described recent decisions by the Ivorian and Ghanaian governments as “very important, especially since price has been left out of the discussion for too long.”

Introduced in 2018, Tony’s Open Chain aims to ‘end modern slavery and illegal child labour in cocoa by setting a new industry standard’: “We promote a higher price, traceability, strong farmers, long-term relationships, higher productivity and less cocoa dependency,” explained Schoenmakers.

Barry Callebaut and Dutch grocer Albert Heijn were the first to latch onto the program last December.

“This is a great move by governments taking the lead, and stands in sharp contrast with the lack of progress Big Choco has made since signing the Harkin Engel Protocol in 2001,” he added. “Big Choco have to take responsibility as well, just like governments, supermarkets and consumers – the five key players – because only together we can change the cocoa industry into a new equally divided economy.”

He insisted, however, that a higher price does not ultimately solve the underlying, nuanced issues at play.

“For a silver bullet solution, you need to control production through 100% traceability, (end deforestation) and [enact] better agricultural policies and practices: more cocoa on less land. That is why we use and promote our five sourcing principles [Tony’s Open Chain], the new rules of the game in our opinion,” said Schoenmaker.

The lack of coordination among players in the value chain remains a prickly thorn in the side of progress, he contended, meaning everyone – not just governments – must take responsibility for their choices and their actions.

Preventing child labor is a global challenge that goes far beyond any single entity. It requires coordinated and comprehensive action by governments (both in countries where products are grown as well as where they end up), businesses and consumers. Only together we can change the cocoa industry into a new equally divided economy. Tony’s Chocolonely exists to prove that it can be done differently. We want to inspire the industry to take responsibility.

International Cocoa Initiative: 'everyone could do more'

It is essential that we place a caveat on ‘mostly theoretical’ studies like the PLOS analysis, ICI’s director Matthias Lange told ConfectioneryNews. He doubts that a 2.8% price increase at farmgate level would suffice. The study – and others like it – have merit that ‘brings interesting perspective,’ he said, but he worries that such ‘microeconomic and not empirical’ examples cannot translate into real-life scenarios.

“I will not argue that increasing the price of cocoa is not potentially a valuable thing. But the fact is that cocoa prices [are] one element of cocoa income, and cocoa income is just an important element of the overall farmer income, and farmer income is one of the underlying causes of child labor – but not the only one.”

As FairTrade discovered, ICI, too, has found examples of farmers receiving premium prices – yet child labor persists.

“A vast majority of child labor takes place on family farms. Sometimes it’s not just a question of poverty. [If they] don’t have the capacity to go to school, then they may just go and contribute to the family force, in order to gain some skills,” Lange told us.

“It’s a bit more complex than simply pushing price increase per ton. [We’ve] had a competitive approach where several elements have been brought together to tackle the issue in a slightly more holistic manner,” he said.

Nuance is equally important when discussing enforcement of child labor policies – notably in the gray areas between what Lange described as family child labor and forced labor.

“Slavery across the sector is certainly something which is out there, and which is a grave violation of human rights and needs to be criminalized. But the overall numbers of children involved – that’s a tiny portion in volume of what we are talking about," he said.

What farmers need is not necessarily policemen, but they need additional support.

Social and community development coupled with interventions in the supply chain can assist identifying where, when, why and how child labor is happening. All stakeholders must play a part ‘in a coordinated manner,’ added Lange; government involvement in providing social services has helped.

“They do a lot, and honestly, when you look at the level of government spending going into those areas, notably education, that’s very significant, but [that] doesn’t necessarily mean that they currently reach absolutely all the children with those services. That’s a journey that’s going to take some time.

“Everyone could do more – and there are a number of actors that can certainly do much more. Anyone that derives profits or simply pleasure from chocolate should also be a part [of] solving the problems.”