Fifty or 60 years ago, John Narh Adamnor’s grandmother planted her land in Ghana’s eastern region with cocoa. She was a Krobo woman, one of the Ga-Dangme peoples who settled the area from the east to today’s capital, Accra. Adamnor is not sure exactly when his grandmother planted the trees, but it would have been a time of optimism around cocoa.

After independence from Britain in 1957, Ghana’s cocoa farmers were the economic backbone of the new nation-state. As Adamnor’s grandmother’s trees were taking root, demand for chocolate was growing in Europe and North America, and cocoa’s price was rising.

“Back at that time … everybody was doing cocoa,” Adamnor explained. “The white men came to buy cocoa, the market came for cocoa.”

Back at that time … everybody was doing cocoa

Other farmers in the area were planting coffee and oil palm, but Adamnor is grateful that his grandmother chose cocoa. “I’m very, very glad, because the trees are up to date. Those who plant[ed] palm trees, they took them all off, but the cocoa is still alive. We depend on it, up to date. So I’m glad that she chose to plant cocoa.”

Adamnor inherited the land from his father when he was 23 years old, splitting the family plot with his elder brother. Their four sisters did not inherit land, so Adamnor committed to looking after his eldest and youngest sisters, while his brother took responsibility for the middle two. All of the sisters are married and have homes of their own. In times of need, though, they can call on their brothers for support, thanks to cocoa.

Before he inherited the land, Adamnor drove a taxi in his hometown, Koforidua, capital of the eastern region. But for the past 13 years, he has farmed his seven acres. I asked him how he thinks of himself now, professionally. “I am,” he said, “a cocoa farmer.”

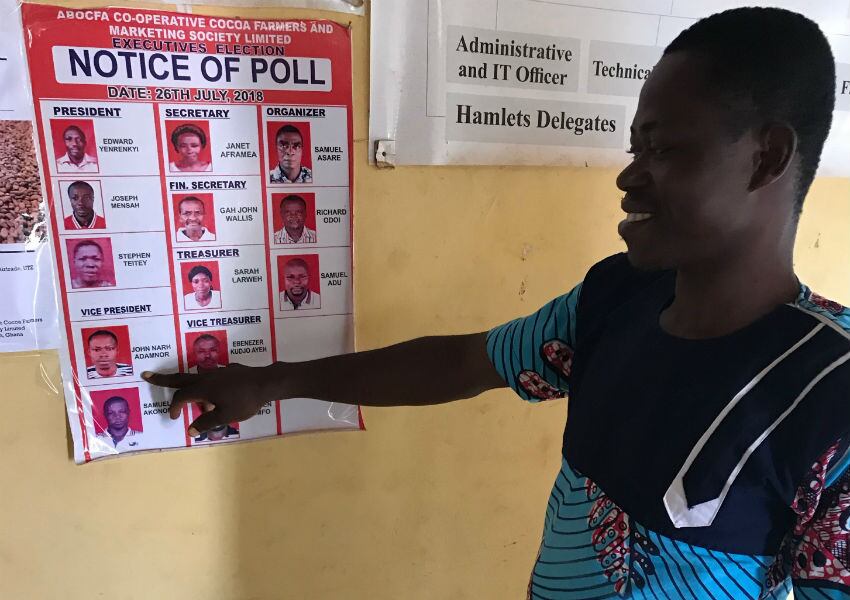

Up until now, Adamnor’s trees have produced about 15 bags of cocoa each year. Since 2016, the producer price for a 64 kilogram bag of cocoa in Ghana has been GH¢475 (US$88). This means that, for a year’s labor, Adamnor has been earning the cedi equivalent of about US$1,300. Because he is a member of the Fairtrade and organic certified cooperative, ABOCFA, Adamnor also receives a premium for his cocoa.

In 2018, ABOCFA paid an organic and Fairtrade premium of GH¢40 (US$7.43) per bag, which gave Adamnor an additional GH¢600 (US$111). He sounded genuinely pleased with the amount, but still described it as “small money,” and emphasized that it doesn’t make his life luxurious. “It’s good, it’s very good,” he said, “but if you get the premium, you are not going to use it to buy meat, fish and enjoy yourself.” Instead, he uses the money—which arrives during cocoa’s light crop in July, when cash is tight—to prepare his farmland for the upcoming main harvest.

When I asked Adamnor what would make cocoa farming easier, he laughed and told me that nothing was easy. He described a cycle, in which it seemed that smallholders like him were perpetually stuck: the only way to make life easier was to do less cocoa farming labor, which is hot and sweaty and involves the ceaseless removal of weeds and tending of trees. Doing less of that labor oneself meant hiring laborers to do it for you.

If you get the large farm, you will get more money

And the only way to get enough money to hire laborers was to have a lot of land in the first place. “If you get the large farm, you will get more money,” he said, “and when you are getting more money, the work is becoming soft for you. Because you get more laborers, [and] the work will go fast.”

Though we met at the start of the rainy season, the skies were clear that morning over the ABOCFA office in Suhum, so I was hopeful of visiting Adamnor’s farm, about a half-hour walk away. But Adamnor told me that it wasn’t a good day for a visit. It was coming up on the Ohum festival, which celebrates the start of the yam harvest. According to tradition, for several days around the festival, it is considered disrespectful to do farm work. If we did go to his farm and were caught, Adamnor would have had to pay the chief a fine of 10 bags of cement, at a cost of GH¢350 (US$65), or more than half of what he had earned in premium money the previous season.

Adamnor didn’t seem too fazed by the work ban. In 2018, he was elected vice president of ABOCFA, and meetings kept him busy. At nine that morning, when I arrived at the office, a staff meeting that had begun at six was just wrapping up. After we talked, Adamnor walked off to join another meeting with a farmer group. Clearly, there was no shortage of other work to do. But still, the week was an important one on Adamnor’s farm. With cocoa trees well over 40, which is the upper end of their commercially productive age, Adamnor needed to replant. Work was being done that week to finish clearing and replanting half his land.

It is not easy for a smallholder to clear cocoa trees and start again, not least because Theobroma cacao can take up to five years to start producing fruit. Ghana Cocoa Board distributes seedlings for free, but there were none available when Adamnor wanted to replant, so he purchased them at 50 pesawas (US$0.09) each, plus another 50 pesawas for a laborer to plant each one: a total of GH¢1 (US$0.18) per seedling.

His preference was for a hybrid variety that matures quickly. “That one, you harvest it [in] just about three years’ time. That’s fast. It will grow very quickly.” The hybrid would also produce cocoa pods year round. “It [has] no season,” Adamnor explained, “every time it is bearing a fruit.”

Adamnor also planned to intercrop his cocoa with Apem and Apentu plantains, which are used to make a starchy base for savory meals, as well as bananas, which are sweeter and eaten as fruit. Each banana also costs GH¢1 (US$0.18) total for seedling and planting, and those trees would mature faster than cocoa. Each acre of land could hold 450 cocoa seedlings and 450 banana seedlings. For the 3.5 acres he was replanting, Adamnor’s total investment in new trees came to GH¢3150 (US$585). He also had to hire four laborers. At GH¢20 per person, per day, Adamnor’s labor costs came to GH¢560 (US$104).

On top of these costs, his cocoa earnings will now be half of what they were, until the seedlings mature. It is possible to plant seedlings amongst old cocoa trees, to retain income while young trees mature. However, Adamnor’s older trees were infected with sasabro (swollen shoot virus), and he could not risk the seedlings being infected. He also wanted to replant trees in straight lines, and would not have been able to do that with the older trees still in place.

Their father is going to the farm, so they want to know what their father is doing

Adamnor thinks of himself as a cocoa farmer, but he would still like to diversify into other livelihood activities, especially raising grasscutters—bush rodents that are a popular source of meat. A mating pair and the cage to house them costs about GH¢1500 (US$279). Grasscutters sell for GH¢120-150 (US$22-28) apiece in the marketplace, depending on size, so he would have to breed and sell at least 10 animals before turning a profit. It’s not an investment Adamnor feels he can make right now.

I asked whether Adamnor wanted his daughters—Lois (12), Silvia (7), and Judith (3)—to become cocoa farmers. He was concerned, as are many people I meet in Ghana, that it is more difficult for women to farm cocoa than it is for men. Because women aren’t considered to have the strength to perform certain farm tasks, they must hire laborers. If you’re a woman, Adamnor said, “you spend all your money to pay laborers.” His children were too young to know what they wanted to be when they grew up, but Adamnor hoped they would choose to become nurses or doctors. For now, they just enjoyed going to the farm with him.

“Just for fun,” he said. “They do nothing.” He began to laugh. “Maybe they fetch water, give me water to drink. They just want to go with their father. Their father is going to the farm, so they want to know what their father is doing.”

Though Adamnor considered cocoa a serious business for himself, I wondered if his reluctance for his daughters to take over the family farm was also because—unlike his grandmother—he didn’t see a hopeful future for smallholders. Land, he insisted, was the main limiting factor to improving his livelihood. “If you get land, then you get money,” he told me.

But he also thought cocoa’s price was too low. Adamnor laid responsibility for this with foreigners who enjoy eating cheap chocolate. “You, the whites, are eating cocoa,” he said. “You bring the price … you have to give us a chance to sell it at the price that we want.” I asked what producer price would make meaningful financial change in his life. “Even at six hundred, oh, it would change things,” he replied. GH¢600 (US$111) per bag would be a 26% increase on the current producer price in Ghana.

At that price, selling 15 bags a year, Adamnor quickly calculated that he would have more than GH¢1500 (US$279) additional annual income—well over double what he earned last year from the organic and Fairtrade premium. With that increase, he could continue to invest in his farm, but also allow for some domestic comforts. “Maybe, if your children are going to school … maybe they are walking to the school, but if you have a lot of money … you will hire a car for them,” he mused. With the prospect of even such modest luxuries, Adamnor thought that “even the youngest will be happy to join a cocoa farm.… If the price is high, all the young will run to cocoa farm. And everybody will take it as a serious business.”

It’s really a peaceful country. We are having a lot of things: cocoa, coffee, timber ..

Adamnor can remember all the times he has bought chocolate—because there have only been two of them. He made both purchases in Accra, buying Kingsbite milk chocolate bars from traffic vendors as gifts for his daughters. He’s never bought chocolate for himself, although he gets to taste it pretty often, when foreigners come to visit ABOCFA. I had brought some milk and dark bars made with Ghana cocoa. Adamnor preferred the dark, but said his daughters and his wife, Hannah, would prefer the sweeter milk chocolate.

After our tasting, I asked what Adamnor would want people to know about Ghana. His answer surprised me. He said that foreigners who visit ABOCFA often see the goodness of Ghana more readily than he does.

He sees more of a mix—much is difficult, but there are also things to be proud of. “Ghana is good,” he mused. “It’s really a peaceful country. We are having a lot of things: cocoa, coffee, timber, even now we are having oil here.”

He paused, and seemed to make a connection between the peace and Ghana’s ability to trade its resources. “We have peace,” he said again. “Even the peace serves.”

About 'Dr Chocolate'

Dr Kristy Leissle is a scholar of cocoa and chocolate. Since 2004, her work has investigated the politics, economics, and cultures of these industries, focusing on West African political economy and trade, the US craft market, and the complex meanings produced and consumed through chocolate marketing and advertising. Her recent book, Cocoa (Cambridge: Polity, 2018) explores cocoa geopolitics and personal politics, and was #3 on Food Tank’s 2018 Fall Reading List.