British chocolatier Hotel Chocolate grows its own cacao in Saint Lucia and sells chocolates direct-to-consumer via physical store, online, and subscription channels.

The brand boasts a revenue of £132.5m (up 14% from 2018) with £10.9m profit after tax, and is expanding its presence into international markets, including Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Scandinavia, and the US.

However, the company started with ‘very modest ambitions’, according to CEO Angus Thirlwell, who describes Hotel Chocolat’s journey a ‘perpetual evolution’ with ‘perpetual growing ambitions’.

From ‘the nichest’ start-up to ‘falling under the spell of chocolate’

Speaking at start-up event Bread and Jam earlier this year, Thirlwell said his initial start-up – which he launched with business partner Peter Harris – was founded on “the nichest idea you’ve ever heard of”.

The concept was to supply customised branded peppermints to corporates, and in doing so, replace plastic branded promotional pens. The B2B model was relatively cash generative, said Thirlwell, “we made it work and got to a few million pounds-worth of sales.”

Once The Mint Marketing Company expanded its concept into chocolate, the business partners observed that chocolate ‘had the power to excite people’ in a way that peppermints didn’t. “There was a very fertile possibility of using imagination to create something interesting,” Thirlwell recalled.

The duo quickly ‘fell under the spell of chocolate’ and started researching the B2C market. Their next offering, which launched in the late 1990s, was the ‘Chocogram’ – a chocolate box that fit through a letterbox with a gift card attached.

While that model worked ‘very well’, Thirlwell felt the company was being held back by its brand name: Choc Express. Further, repeat custom was infrequent. In 1998, the partners integrated the Chocolate Tasting Club into the business, whereby subscribers received mixed selection chocolate box every month.

Two years later, Choc Express began to ask subscribers to score the chocolate recipes – a concept that still exists today. With approximately 100,000 members, the company was now ‘modestly profitable’, said Thirlwell, and “at a point where we [needed] to get a proper brand name”.

Hotel Chocolat takes the brick-and-mortar plunge

Having spent time in France, Thirlwell was convinced he wanted the French word for chocolate, ‘chocolat’, in the brand name. And the word ‘hotel’ offered the promise of a place, he elaborated. “A hotel is a refuge, it’s somewhere that people look forward to going to. Putting the two together created some kind of magic.”

It was at this time that Hotel Chocolat established its three pillars – “the three things that we wanted to focus on forever, as a brand and a business”. These are originality, authenticity, and ethics.

CEO Angus Thirlwell on Hotel Chocolat’s three pillars

Originality: “We want to be continually driven by imagination. Doing things in a fresher, better way, and not copying other people or following, in our case, Belgian chocolate, Swiss chocolate, or French chocolate.”

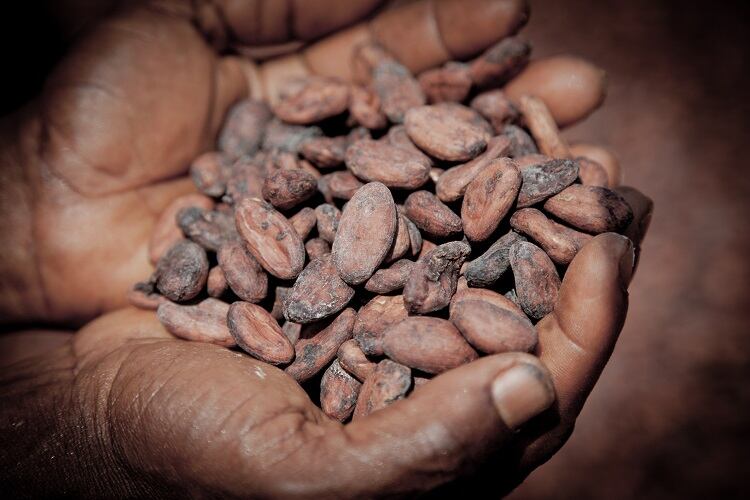

Authenticity: “We have gradually been putting more and more cocoa, and less sugar, into our chocolates. We also want to be ‘the real deal’ in terms of knowledge. This is what ultimately led us to buying our cacao estate, because we needed to know absolutely everything about the star ingredient: the cacao.”

Ethics: “Ethics [is about] being a good world citizen, going about things in a responsible way, [including] the way we do deals with suppliers and pay on time, through to making sure that all the cacao we use [is aligned with] ‘engaged ethics’ – which goes beyond broader [sustainability] programmes.”

Hotel Chocolat is also committed to reducing waste, using ‘every part’ of the cacao bean, such as the cacao shells which it uses in infusions. Any misshapen chocolates that are made with premium ingredients go into the company’s reduced-priced ‘Ugly But Good’ bags.

Hotel Chocolat’s ambition again ‘notched up’ a level when it took the plunge into brick-and-mortar retail, said Thirlwell. Creating a branded Hotel Chocolat space addressed the immediate gratification element of chocolate, he explained. “Not everybody is prepared to wait a day for their chocolate to arrive. When you decide you want it, you want it right now – and we were not providing a solution to that.”

The retail model ‘really started to work’, attracting a broader demographic compared to the company’s online subscription model. The team also observed that physical retail played a ‘huge role’ in building brand awareness.

Some call brick-and-mortar outlay ‘rent’, but the self-proclaimed ‘big fan of physical retail’ said it can otherwise be interpreted as ‘marketing’: “It’s the cost of acquiring a new customer.”

Since opening that first store in 2004, Hotel Chocolat has amassed 115 stores in the UK.

Becoming a British cocoa grower

In 2006, the duo made their foray into the cocoa growing world, with the acquisition of Rabot Estate – a 250-year-old cocoa plantation in Saint Lucia.

In doing so, Thirlwell hoped to raise consumers’ awareness of the entire chocolate production process – starting on the farm. “Nobody ever talked about [the agricultural side],” he recalled. “Unlike wine or olive oil, the agricultural discussion is never there. And therefore, the potential profits from a successful consumer good doesn’t make it there either.”

Not only would purchasing a cocoa plantation be ‘an amazing business adventure’ that would help build a ‘stronger brand’, but Thirlwell was also convinced they would be “doing something good that would nourish the ethical and authentic elements of [the] brand”.

Buying Rabot Estate has enabled Hotel Chocolat to build up knowledge in the entire chocolate making process, including how to grow cacao organically, how to preserve old gene types of trees, and how flavour can vary from grove to grove.

In 2011, Hotel Chocolate opened a hotel and restaurant on the estate. Thirlwell estimates 70% of the guests come from the US. Having coincidentally launched in the US in 2018, the CEO predicts the hotel will be ‘more valuable than expected’ in terms of reaching US-based audiences and ‘creating a new narrative’ on chocolate.

Next steps: The reinvention of (hot) chocolate

Hotel Chocolat aspires to ‘reinvent’ chocolate. Part of this mission is encouraging consumers – and brands – to pay close attention to

ingredients lists.

As such, the brand is campaigning for tighter regulations regarding how the term ‘chocolate’ is used. As it stands, its meaning is ‘quite loose’, he said. “In my book, it’s quite easy. If cocoa is the number one ingredient [in a product], you can use the word ‘chocolate. If sugar is the biggest ingredient, then there is another word that is available: it’s ‘confectionery’.”

The CEO said he is asking chocolate associations to ‘tighten up’ rules regarding its use. “Mixing [‘chocolate’ and ‘confectionery’] up has done a good job of confusing the customer for decades. I think chocolate associations should do a better job of providing guidance for the consumer.”

Another of Hotel Chocolat’s missions is to reinvent hot chocolate. “We are trying to bring back the reference of drinking chocolate that used to exist in the 1700s in Europe, and before that, in early Mayan civilisations,” explained the CEO.

The brand’s current range includes single serves of grated hot chocolate products, in flavours such as salted caramel and clementine; 100% Mayan red Honduras, and maple and pecan.

“We’ve got to get people to stop thinking about hot chocolate as an instant powder full of sugar, skimmed milk, and a tiny bit of cocoa powder, and instead – as coffee has done very successfully – bring it back to this noble drink that is full of good nutrients.”