Special Report

Cote d’Ivoire’s cocoa sector looks to the future with a shift towards sustainable agroforestry

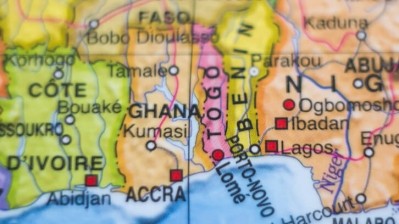

The West African country contributed 46% of the global cocoa output in 2021-22 but in a major policy change, its government has stated it has no intention to increase production beyond 2,000,000 kilotonnes (KT) and in 2018, banned the planting of new cocoa trees in a bid not to saturate the export market and bring prices down.

“Our programme for the period 2021-2025 will accelerate Côte d’Ivoire’s economic and social transformation, with an even bigger involvement of all stakeholders, including the private sector and civil society, for even more inclusive growth and a more united Côte d’Ivoire,” said President Alassane Ouattara, speaking at the launch of the country’s National Development Plan late last year.

The cost of the government’s action plan is estimated at approximately 700 billion CFA francs, or more than 2 billion euros over the next decade.

What does the policy change mean for the cocoa industry?

Barry Callebaut’s Agronomic Center is located near the town of Tiassale, 130km northwest of Abdijan in one of the country’s main cocoa-growing regions.

For the past five years, it has been growing plant and shade seedlings for distribution to farmers in its Forever Chocolate sustainability programme in two nurseries producing 500,000 seedlings per year including: Akpi, Framire (yellow wood), Fraké, Mahogany, Bété and Avocado.

For us, a traceability system being developed, owned and managed by governments is a key solution and we fully support that -- Nicolas Mounard, VP Sustainability and farming, Barry Callebaut

Christoph Julienne is the Sustainability & Cocoa Sourcing Manager for SACO (Societe Africaine De Cacao), which is part of the Barry Callebaut Group and its face in Cote d’Ivoire.

He oversees agronomic research at the center, where, he said, different trials are taking place to find practical solutions linked to cocoa yield enhancement with agroforestry and soil fertility.

He explained that the two nurseries are maintained on a daily basis by approximately 20 women and the 42 ha facility started its operations in 2016.

Around 30 ha is dedicated to research with multiple partners, and we were taken to a demo farm that Barry Callebaut is managing with Mondelēz International experimenting with various shade and fruits trees to ascertain which works best with cocoa trees in terms of providing cover, offering the farmer extra income, while at the same time not diverting essential nutrients and moisture in the land from the valuable cocoa tree.

Along with the 3 ha dedicated to seedling nurseries, 7 ha is dedicated to good agricultural training and after our visit to the centre, the overriding impression is that of a paradigm shift in policy not only for Barry Callebaut but perhaps the whole cocoa sector in general, particularly in West Africa, as it prepares to comply with new EU legislation that will come into force in 2025, decreeing that 100% of cocoa will require full transparency of not being grown in protected areas - or from regions where evidence of deforestation has occurred after December 2020 - if it is to be allowed to be imported into the region.

Cote d’Ivoire’s National Development Plan

Climate change and the requirements of the energy transition are major challenges that Côte d’Ivoire is now facing.

Cocoa accounts for 40% of Cote d’Ivoire’s export incomes and 15% of its GDP. The country’s National Development Plan has set out a target to increase agricultural production by 7.5% by 2025, but with no additional land available due to its reforestation commitment to move from 9% forest to 20% forest, its 2,000,000 tonnes of cocoa will have to be produced on less land as part of the government’s modernising agenda.

President Ouattara said the threats are real, ranging from floods, disruption to rainfall patterns, coastal land loss and rising temperatures, which could jeopardise agricultural production and put cities such as Abidjan or Grand-Bassam at risk.

“Rapid deforestation is a problem, as tropical forests play a crucial role in combating local climate change and regulating rainfall temperature. The national priority is restoring forest cover to 20% by 2045, which equates to almost 3 million hectares of forest,” he said at a news conference for the launch.

The good news is that the self-imposed cocoa cap of 2,000,000 tonnes will remain at the same level for the next five years so it won’t necessarily cause a shortage of the crop on the world market.

With large agri-business companies like Barry Callebaut having to re-evaluate its Cote d’Ivoire operation in the light of new domestic and international legislation, it is clear that cocoa needs its own modernising agenda and making sustainable chocolate the norm requires a concerted effort with more collaboration from the entire industry.

“When we define our mix of non-cocoa trees we need to take different things into account,” Nicolas Mounard, VP Sustainability and farming, Barry Callebaut, told ConfectioneryNews.

“We take carbon as an element and carbon sequestration is one element, but we also look at other elements like food production. A lot of farmers are planting fruit trees – a lot of plantain in Ivory Coast - as well as avocado and we look at income diversification potential and we look at timber so in general we try and make a balanced choice between the elements.”

Barry Callebaut’s Forever Chocolate sustainability programme is to be reset with a major launch later this month with new policies to reflect new priorities in light of environmental and regulatory pressures and is expected to call for a more action-based approach to generate a higher level of investment in the cocoa farm.

Barry Callebaut’s Agronomic Center, therefore, is crucial to its future commitments of facilitating access to planting materials, fertilizers and offering agricultural training in pre-harvest labour.

In 2022, the group reported that 50 ha of reforesting took place in Côte d’Ivoire’s Agbo 2 Forest to protect one of the world’s most biodiversity-rich and fragile ecosystems while supporting cocoa farmer livelihoods.

In the past year it has distributed 30’000 ha Fertilizer+ phyto and has included 48’000 farmers in its Farmer Business Plan, to facilitate credit and loans for costs and materials while developing 11 nurseries for agroforestry and distributing and planting 2.8 million seedlings.

In its direct sourcing supply chain, end-to-end traceability is provided by the Katchile Traceability Module, which captures data in systems from the farm to the export to consuming countries. So far, it has mapped 85% of its suppliers in an area covering 377,426 ha, which guarantees the cocoa has been sustainably sourced. It claims that in the previous year, out of 267,000 mt of coca beans, 91% were sustainable sourced through Barry Callebaut's independent Cocoa Horizons certification programme.

Mounard said Barry Callebaut is fully supportive of sharing this data, and believes that in Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, traceability should be government-led.

“We have been asked to share 100% of our polygon data with the CDI government. We acknowledge there is a lot of overlap between private companies – we end up mapping the same plots, and some farmers supply different volumes to different players. For us, a traceability system being developed, owned and managed by governments is a key solution and we fully support that.”

The new Forever Chocolate charter is expected to confirm that Barry Callebaut is on track to be Forest positive by 2025, meaning its traceability will guarantee no beans in its supply chain will be associated with deforestation and that since the commencement of Forever Chocolate in 2016, it has reduced its overall corporate carbon intensity per tonne of product by more than -17%.

Moving beyond 2025, Barry Callebaut will align its environmental policies with the Paris Agreement on climate change and is already actively participating in action-oriented business coalitions, public private partnership between the EU, cocoa origin countries and industry in order to accelerate the transition towards sustainable business models.

While the emphasis on companies like Barry Callebaut is on helping smallholder farmers to increase resiliency, yields and improve livelihoods, there is also pressure at the corporate level to create incentives to draw down additional carbon.

Mounard recognises the need to balance its carbon agenda with the incentives of farmers, in terms of income and food production.

“When it comes to adoption, what we have observed in the last two years is that the carbon agenda is something that we were putting on the farmer and was not necessarily coming from them so we acknowledged that it was important to develop an ... ecosystem payment service where the farmer is paid for the ecosystem service they provide to the environment,” he said.

“We have factored that into our approach over the past 12 months – 50 euro per year per hectare – over 10 years to create the alignment between the agroforestry model and the interest of the farmers.”