“When Kristy and I took a look back at the work we did together — combining our chocolate confectionery and cocoa backgrounds on a single project — we realised we had an important story to tell the industry. I was always personally baffled by all the talk around cocoa stock market price, FOB price and farm gate price,” Beach tells ConfectioneryNews.

“I knew exactly how things operated in Madagascar, but it was not until we had explored possibilities in Ghana that I realised how that system differs and why so much confusion is created around discussions of living income and the impact of Fairtrade.”

Brett Beach

My path to Ghana and the heart of global cocoa production was anything but direct. But after more than 15 years in the chocolate confectionery industry, I am suddenly grappling with issues, opportunities and challenges I had only previously observed from the sidelines.

I came to know (a small part of) Africa as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Anjozorobe, a village in the central highlands of Madagascar. After my Peace Corps service, and four more years in various development jobs, I was yearning for home, but not yet ready to leave Madagascar behind.

In 2006, I co-founded a chocolate business that would become a brand called Madécasse. I dedicated the next 10 years of my working life to telling the story of Madagascan chocolate to those who would listen in the US and Europe.

In 2016, I decided to move on from Madécasse, and co-founded a new brand called MIA. MIA stands for “made in Africa,” and its vision is to make value-added food products in Africa. We started with a range of bean-to-bar chocolates made in Madagascar, and then decided to expand to a second country. Enter Ghana.

In the chocolate world, Ghana and Madagascar could not be more different. Whereas Madagascar grows fine flavour cocoa that sells on a niche market, Ghana is the number one origin for high-quality bulk cocoa and is traded on the futures exchange. Madagascar produces less than 1% of the world’s cocoa, and Ghana is the second largest producer.

When it comes to cocoa economics, the biggest difference between the two countries is the management of the cocoa industry. In Madagascar, chocolate companies can buy directly from cocoa farmers without any middle trader. In Ghana, government regulator Ghana Cocoa Board (Cocobod) is responsible for all sales of cocoa beans -- Brett Beach

Madagascan farmers utilise box fermentation – or do not ferment at all – while farmers in Ghana do heap fermentation on their own farms. Madagascan cocoa is known for its citrussy acidity and delicate notes of red fruits, whereas Ghanaian cocoa tends to be rich and bold, with a classic chocolate flavour.

When it comes to cocoa economics, the biggest difference between the two countries is the management of the cocoa industry. In Madagascar, chocolate companies can buy directly from cocoa farmers without any middle trader. In Ghana, government regulator Ghana Cocoa Board (Cocobod) is responsible for all sales of cocoa beans.

When we set out to create a second range of chocolate, we started with little understanding of the cocoa landscape in Ghana. To overcome our inexperience, we collaborated with Dr Kristy Leissle, a researcher who was based in Ghana at the time. Kristy evaluated farmer groups that could be long-term partners for MIA, and align with our focus on an ethical supply chain.

After 18 months of virtual meetings, innumerable text messages, cocoa testing, farmer interviews, chocolate prototypes, and an eye-opening site visit, I have gained perspective on what it takes to make chocolate from bean to bar in Ghana.

Cocoa farmers in Madagascar generally earn well above Fairtrade prices for their fine flavour beans, but Ghana presents a more nuanced market. Cocobod acts as an intermediary between cocoa farmers and international buyers, setting the farmgate and FOB (Free on Board) prices.

Thanks to Cocobod’s organizational strength and service provision, Ghana’s cocoa farmers produce what most traders consider to be the highest quality and most reliable bulk cocoa. The flavour of these beans is quite literally the flavour of chocolate.

But what do the farmers receive, for their excellent cocoa? I’ll turn it over to Kristy now for a discussion of price.

Dr Kristy Leissle

Most cocoa farmers struggle to earn a living income from their crop. It would seem that the most direct and impactful way to change this would be to increase the price paid to farmers. And I applaud my colleagues in this industry who advocate for a radical upward revision to cocoa pricing.

I too want farmers in Ghana – and everywhere – to earn much, much more for their hard work, which I have borne witness to for 18 years as a field researcher. Yet as contradictory as it may sound, there are many reasons why price is not the ideal vehicle for improving farmers’ livelihoods, at least in Ghana’s current trading system.

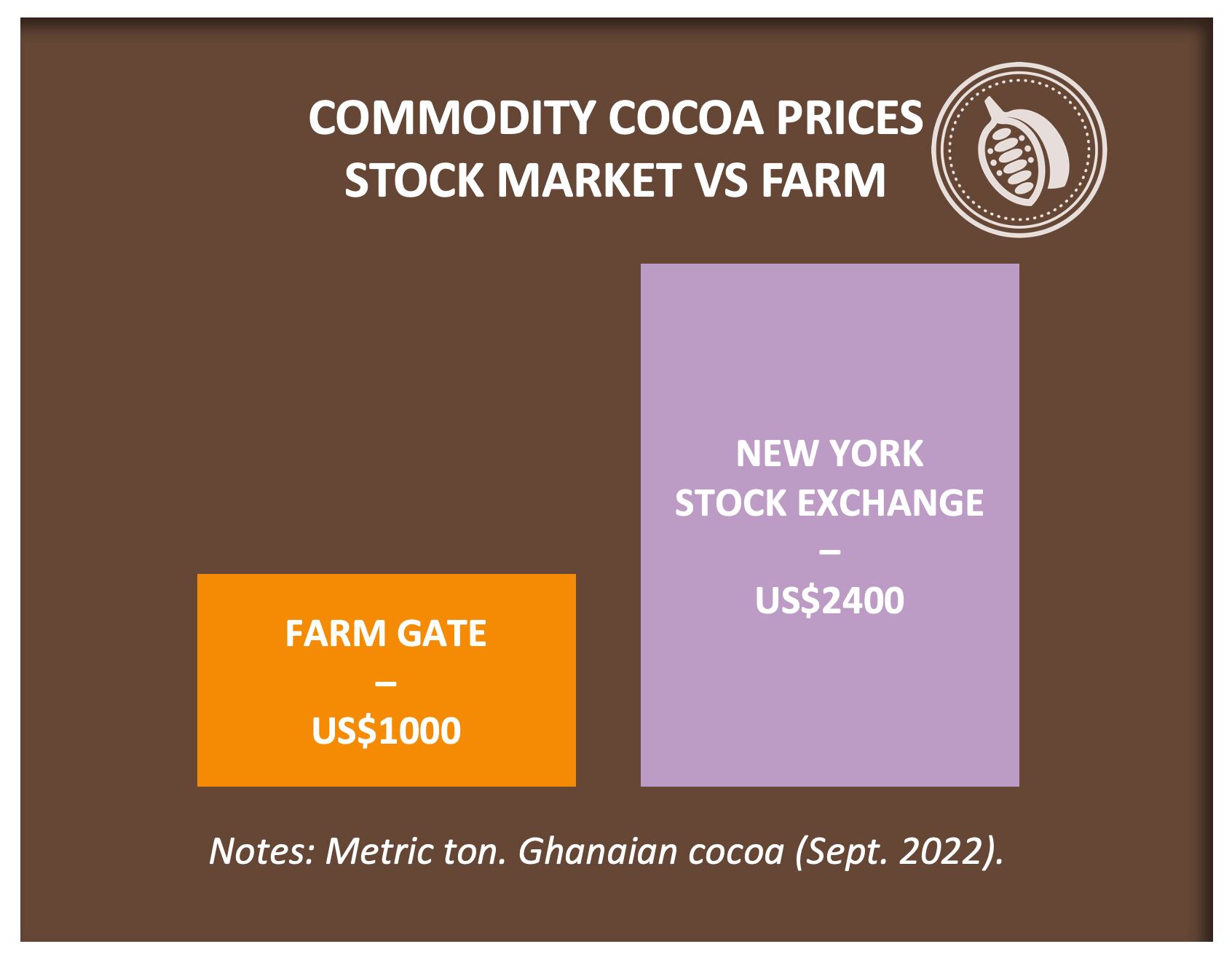

First of all, let’s clarify what we mean when we talk about cocoa’s “price.” Are we referring to the world market price, which is cocoa’s trading price on the New York and London futures exchanges? These prices are easy to find, as the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) publishes them daily.

When taking into account Ghana’s high-quality cocoa, cocoa farmers there are paid a shockingly poor producer price -- Dr Kristy Leissle

Cocoa closed out August 2022 trading at US$2404 per metric tonne on the NY futures exchange. This was a very small bump on the daily price average for the month, which was US$2377.

An important reason for the slight price rise was the announcement that Ghana’s cocoa crop for the 2021/22 season was down 35% from the season prior. The reasons for such a drastic fall were a combination of drought conditions; rampant swollen shoot disease in certain parts of the country; and a loss of cocoa farmland to illegal gold mines, called galamsey.

In fact, the ICCO predicts that the 2021/22 season will end with a global deficit, meaning that worldwide demand for chocolate will outstrip this year’s cocoa supply. The organization also suggested that, owing to supply chain challenges, farmers in Ghana will have more difficulty accessing fertilizers and other important inputs in the coming year, which may compromise both the volume and quality of Ghana’s crop.

With these cocoa supply difficulties looming, the world market price is likely to see some gains, however small, between now and the end of the year.

Let’s think about that for a moment. The world market price for cocoa is likely to go up. This is what we all want, right? For cocoa’s trading price to increase? Well, yes, we do, but not for these reasons.

As a rule, the price for when something goes up is when supply goes down and/or demand goes up. Both are happening right now for cocoa. But if you are a cocoa farmer in Ghana, the news that cocoa’s world market price has risen is NOT good news, because it’s based largely on the fact that you have less cocoa to sell.

Ghana’s farmers grew 35% less cocoa this past season. The recent small world market price rise has been nowhere near enough to make up for this loss.

Even if the world market price were to go up by 35% or more, it still wouldn’t balance out the volume loss for Ghana’s cocoa farmers. That’s because they are paid a set price, called the producer price, which is fixed by Cocobod. (Brett refers to the producer price in this article as the “farmgate price”; in Ghana’s case, both terms refer to the same thing.)

Except in very unusual circumstances, Cocobod fixes the producer price for the duration of the main harvest season, which opens annually in October and closes in May (with a light crop continuing through August/September). (This is very different to other agricultural goods, whose price will rise and fall over a season. See, for example, why Bahati Sanjingu, a cocoa farmer in Tanzania, waited to sell her rice until the end of its harvest.)

Cocobod announces the producer price at the start of every season, both per metric tonne and per bag (every bag is standardized to 64 kilograms (kg) gross weight). It is announced in print media, online, on television and radio, and at buying stations up and down the country. Without exception, every cocoa farmer I have ever spoken with in Ghana has been able to tell me the producer price. As far as market information goes, it’s as universal as it gets.

For the 2020-21 season, Cocobod raised the producer price from the 2019-20 price of GHc515 per bag to GHc660 per bag: a 28% increase. This was the first year that the Living Income Differential (LID) went into effect.

The LID is a price premium of US$400 per metric tonne attached to all cocoa sales from Ghana and Cote d’Ivoire, by their respective marketing boards. The goal was to improve farmers’ incomes and move them closer to living income targets.

The increase to producer price in Ghana for 2020-21 effectively passed on more than the full amount of the LID to farmers. (To pass on the full US$400 per metric tonne LID premium, Cocobod would only have had to raise the producer price by 21%.)

Naturally, Ghana’s cocoa farmers welcomed the producer price increase at the time. But their good price fortune ended there. For the next season, 2021-22, Cocobod did not raise the producer price. Farmers in Ghana still received GHc660 per bag.

As we all have experienced, inflation is plaguing the global economy. The UN estimates a global inflation rate of 6.7% for 2022. Ghana’s rates are worse than most: inflation there is at its highest rate in nearly 20 years, at over 30%. Prices of food, fuel, and other basic necessities are soaring.

Moreover, the US dollar is strong, and the Ghana cedi has depreciated severely: when I left Ghana in December 2021, the exchange rate was about GHc6 to the dollar; today, the rate has nearly doubled, to about GHc10 to US$1.

What does this say about Ghana’s cocoa producer price? In dollar terms, Ghana’s cocoa farmers are earning about US$66 per bag, compared to about US$100 per bag before the dramatic devaluation of the cedi. This works out to just over US$1 per kg (US$66 for a 64kg bag gross weight).

Farmers don’t get paid in dollars – but Cocobod does. The marketing board sells cocoa contracts denominated in US dollars. In effect, Ghana Cocobod has earned dollars that are now worth almost twice as much in Ghana cedis, while paying farmers the same cedi amount for their cocoa.

That may change if Cocobod raises the producer price for the 2022-23 season when it opens in October. But let’s face it: this devaluation of cocoa farmer earnings came on top of an already low price, one of the lowest in the industry. When taking into account Ghana’s high-quality cocoa, cocoa farmers there are paid a shockingly poor producer price.

And now for the difficult part that no one wants to hear: unless you are Ghana Cocobod, you cannot change the price paid to farmers for their cocoa.

It does not matter if you have a Fairtrade or direct trade contract, or are a specialty or certified organic buyer. The price is the price is the price.

Literally the only way to pay a farmer in Ghana a higher price for a bag of cocoa is to go to the bush, hand over a higher price to the farmer in cash, and put the sack of cocoa in your car. And keep the transaction secret, because what you did would have been illegal.

Why, then, you might ask, do specialty traders, Fairtrade brands, or organic chocolate companies claim to be paying a higher price for cocoa? To be clear, they are not lying. These companies do pay more for cocoa. And some of that does make it to the farmer. But the higher amounts they pay does not change the price paid for a bag of cocoa to a farmer in Ghana.

Instead, these additional amounts are delivered to farmers through a premium mechanism, which works like a bonus. Premiums are not paid at the moment when a farmer sells a bag of cocoa. They are paid typically once per year, almost always after the cocoa main harvest has ended, and the producer organization has a record of the total amounts that every farmer has sold that season.

(It’s worth noting that if there is cocoa remaining after orders for certified cocoa are fulfilled, the leftover cocoa gets sold as conventional – and the producer organization would not earn any premium for it.)

Farmers don’t earn premiums on every single cocoa bean they grow – and again, this is true whether a farmer participates in a Fairtrade or organic certification scheme, or any quality control project. They are paid premiums only for beans that are designated export quality.

Every farmer will have a record of how much export-quality cocoa they sold in the season prior. Based on that record, once a year they will be paid a “bonus” that reflects some proportion of the premium amounts paid by certified and trade-justice-oriented chocolate companies.

What do I want you to take from this price discussion? Mainly that there is not a lot of room in the system for addressing farmers’ living income challenges through price. While Cocobod’s fixed-price mechanism has many benefits for cocoa farmers (universal price knowledge and payment enforcement being big ones), it leaves few options for the private sector to address living income through price adjustments.

Having just written many words about price, I close with a call to every stakeholder who cares about cocoa farmers, not to pay less attention to cocoa’s price, but to pay more attention to every other option we have to intervene in an unjust system, and make a material impact that farmers will feel in their everyday lives.

Brett Beach

At MIA, we answered this call to find other ways – in addition to paying price premiums – to ensure that the farmers in Ghana who supply cocoa for our chocolate get the attention and interventions they deserve.Working with Kristy, we analysed data from over 1,000 farmers in Ghana, to understand their specific constraints and needs.

According to Fairtrade, farmers in Ghana would need to receive a farmgate price of US$2.10 per kg to achieve a living income; as Kristy explained, currently they are receiving the cedi equivalent of about US$1 per kg before any price premiums / bonuses are taken into consideration.

The fixed producer price is the key to that calculation, and that price is not something we can change. But at MIA we feel it is important to know what other circumstances constrain farmers from earning a living income. Yes, the producer price is the most immediate factor, because it dictates how much a farmer receives per bag of cocoa. But how many bags of cocoa can a farmer grow to begin with? That question, for us, is at the heart of the matter.

Our analysis showed that, on average, farmers in our sample had fewer than 1.5 hectares of land to grow cocoa. Though they reported productivity that was close to the Fairtrade benchmark of 800kg per hectare, the average plot size was too small to generate a living income for a family of six. (This is detailed in the research paper No Silver Bullets.)

Assuming US$1 per kg and 1200kg of cocoa on 1.5 hectares, the average farmer would earn US$1200. This is about one quarter of the living income benchmark of US$4730 that Fairtrade sets for families of six in Ghana (see Fairtrade Living Income Reference Prices for Cocoa). This challenge increases with each generation, as plots of land are divided among siblings upon inheritance, resulting in smaller and smaller farms.

Having gained a better understanding of the challenges that farmers in Ghana face, we worked to find ways to improve their livelihoods. We could not change the farmgate price – the producer price – so we decided to pay a premium of US$360 per ton, which is 150% of the Fairtrade premium (currently US$240 per ton).

We also use our 1 for Change fund to undertake development projects in farming communities. (We fund 1 for Change with a portion of MIA sales.) This programme allows us to be flexible and respond to community needs, whether it be to combat COVID-19, improve schools or provide adult literacy classes (all projects we’ve implemented in Madagascar).

Like the increased cocoa premium, 1 for Change projects have value; taken alone, however, they will not fill the huge gap that cocoa farmers face to achieve a living income.

Field interviews that Kristy conducted showed that many farmers turn to jobs as taxi drivers, cleaners or food vendors, among others, to support themselves. If a farmer is forced to do two or three jobs to make ends meet, the system is clearly not sustainable.

Looking at the challenges linked to land, productivity and price, it is hard not to admit a harsh reality; farmers are at the base of the chocolate supply chain and have little negotiating power individually. Unlike large cocoa traders who dominate the market, farmers cannot protect their profit margins (see recent Confectionery News article, Cocoa prices fall on news of excess supply in Cote d’Ivoire, demand remains ‘mixed’).

The reality is that after more than 20 years of Fairtrade, the average cocoa farmer in the two largest cocoa-producing nations – Cote ‘Ivoire and Ghana – is yet to achieve a living income.

I believe that it is time to consider the bigger picture in chocolate confectionery. Farming is fundamental to the industry, and we need to make every effort to improve farmers’ circumstances. But we also need to look at other ways to create value in cocoa-producing countries.

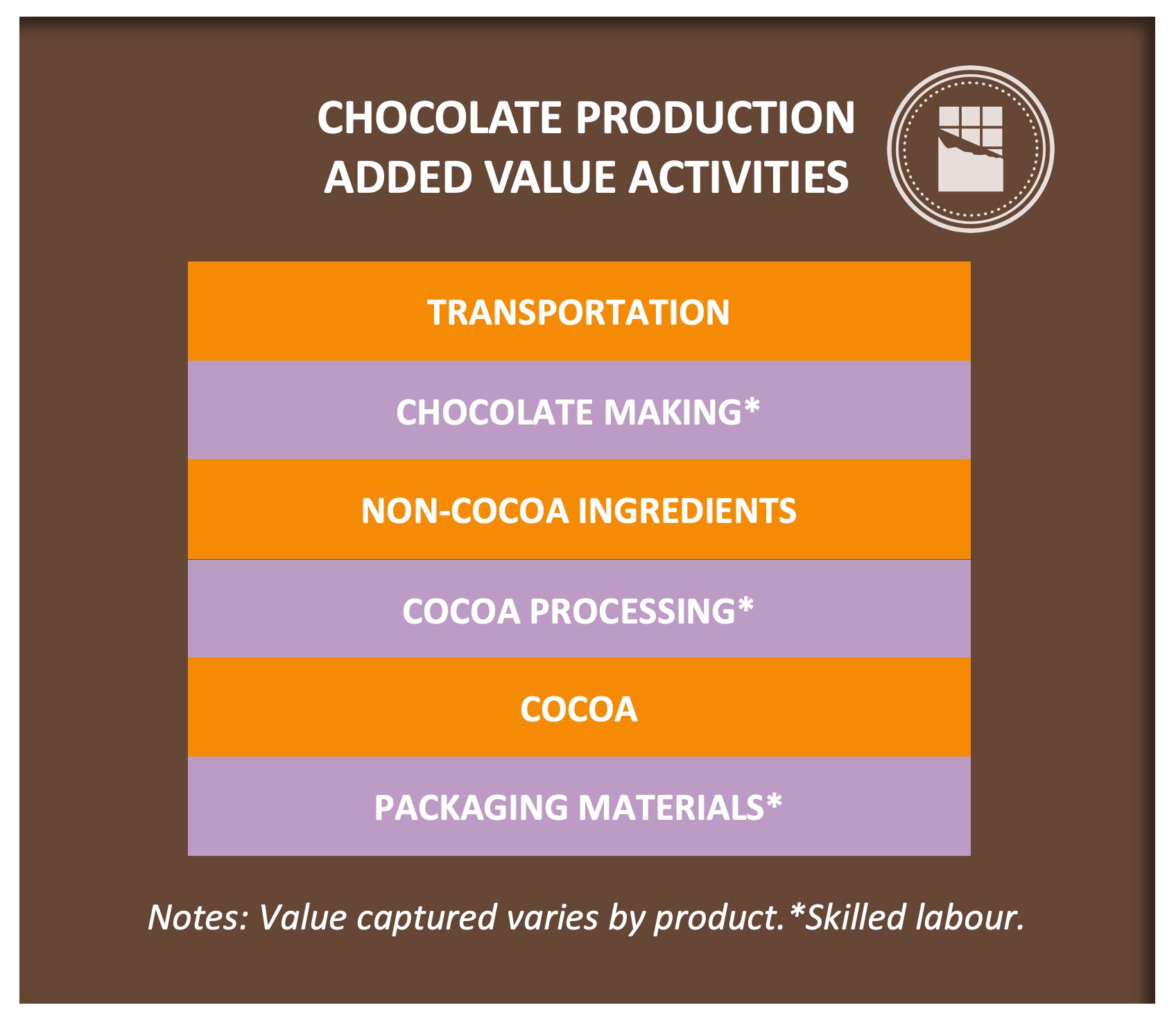

Everyone knows the adage, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” This insight can be applied to the manufacture of every product we enjoy, and chocolate is no exception. It is not just the ingredients and materials that create value. The transformation (labour) that binds these parts into a finished chocolate creates value that has historically taken place beyond the borders of cocoa-producing countries.

In fact, today less than 1% of retail chocolate bars are produced on the African continent, even though African farmers grow 70% of the world’s cocoa. It doesn’t make any sense, but it’s the reality.

The chocolate confectionery industry needs to continue work with cocoa farmers to find the best way forward to achieve a living income, but it’s also time we take a more holistic view that goes beyond the farm gate. We need to support skilled jobs that create new opportunities for the next generation of African talent.

Why can’t the Fairtrade Foundation introduce a certification that recognises and promotes value-added, shelf-ready chocolate products, made in cocoa-producing countries, that create impact beyond the farm? Why not call it “Fairmade”?

Editors note: This op-ed raises answers many important questions, if you also have an opinion on the topics raised, please comment below.

- Brett Beach is Co-founder of MIA, a company that produces bean-to-bar chocolate in Africa to create more prosperity at cocoa origins and raise the status of the continent.

- Kristy Leissle, PhD, has researched and written about cocoa and chocolate since 2004. She is Affiliate Faculty at the University of Washington Bothell, and Co-founder of the Cocoapreneurship Institute of Ghana.